By Venise Toussiant, Paige Westin and Shannon Lins

When he came to Syracuse, Dominic Mathiang never thought he would have trouble with the weather.

"It was very difficult for me," Mathiang said. "That was my first time experiencing snow, I've never seen it before." Considering what he’d been through to get to the Syracuse snow, however, you could bet he would handle it.

An Arab militia kidnapped him in 1988 from Sudan when he was eight years old. He escaped but had to survive on his own in Ethiopia. Four years later, he found his way to a refugee camp in Kenya, more than 1000 miles away from home. In 2004, The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, sent 3,400 Lost Boys to the United States.

Mathiang was one of them.

The “Lost Boys of Sudan” are a group of refugees who escaped from the civil war in Sudan. They are referred to as “lost” because these young men had to flee without their families.

In a new and unfamiliar place, Mathiang reconnected with his childhood in Sudan through The Sudanese Lost Boys of Syracuse Cow Project.

In a new and unfamiliar place, Mathiang reconnected with his childhood in Sudan through The Sudanese Lost Boys of Syracuse Cow Project."The first benefit and the vision of the project was to bring us together as Lost Boys," Mathiang, now 28, said. "…we used to be together at the refugee camps, we used to play together, make stories together, dance together but when we came to the U.S everything depends on you alone."

(Photo courtesy of syracuse.com/to watch a syracuse.com video about the Lost Boys Cow Project Click Here)

David Turkon, assistant professor of Anthropology at Ithaca College, started the Cow Project five years ago in Phoenix, Ariz. While working at the AZ Lost Boys Center, he brought clay for the Lost Boys to sculpt. He said he was amazed to see one quickly create a beautiful miniature cow.

"The whole idea behind it is you know when these guys come here they are children. They grew up in a culture that revered livestock raising and would emulate adults by molding clay cows," Turkon said.

To Mathiang, cows are a powerful image from his past.

"Cows mean a lot in my culture. Cows are just like a form of money, it is more than life," he said. "...if you are born in the society as male, the first lesson you get when you are able to learn is to take care of cows."

Turkon began to market the sculptures at the AZ Lost Boys Center. The money was used for the boys' education in the United States. In the first year, the center raised $30 thousand. When he took a job at Ithaca College in 2005, he wanted to start a similar program in Central New York to bring the Lost Boys together.

"The [Sudanese] community here wasn't very strong and there were some problems with it. They were not seeing themselves as a community," he said.

Turkon said the main problem in the Syracuse area is the assumption that all Lost Boys have the same background.

"There is some factionalism within the community. People think of the Lost Boys as one and the same but there are different ethnic groupings."

In Syracuse there are many tribes, some being the Dinka and DaDinga tibes, McMahon said.

Mathiang is Dinka, the majority tribe in Southern Sudan.

Turkon joined the Central New York Lost Boys Foundation, where he is currently a Senior Advisor. He introduced the Cow Project to fellow advisor Dr. Felicia "Faye" McMahon, a professor of Anthropology at Syracuse University and an expert on Sudanese refugees.

She supported the Cow Project and received a grant through Syracuse University to purchase clay, brushes, and glazes.

Feats of Clay also donated materials for the Cow Project, said Maria Dawson, the owner of the pottery studio in Manlius. The studio invited the Lost Boys of Syracuse to use its kiln and materials to make the cows.

"For a while we were selling the cows here. We were able to get them the glazes and things," Dawson said.

The group had the materials but was looking for a more permanent home for the program.

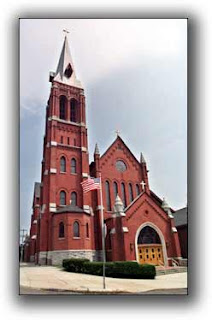

A fellow advisor, Carl Oropallo had a solution. In addition to his job as a lawyer, Oropallo is the Director of Ministry Services at St. Vincent de Paul Church on Syracuse's North Side. The Warehouse at Syracuse University donated a small kiln, which Oropallo installed at the church, McMahon said.

Since its first meeting last January, the Cow Project has grown to an organization of about 15 members, Turkon said.

The Lost Boys meet Saturday mornings at St. Vincent de Paul Church in Syracuse.

The Cow Project itself means more than the money to the Lost Boys, Turkon said. Cows are part of their culture and past. They mold the cows from clay, fire them in a kiln and paint them with colorful designs. The cows stand only a few inches high and are created with many different colors, patterns and designs.

The cows do not have a set price. Instead, they are given as a "thank-you" for donations.

"People would donate 20 dollars and they would get a little cow," Dawson said.

The Syracuse Cow Project does make money but it does not compare to the $30 thousand in Arizona, Turkon said.

Unlike many organizations such as the John Dau Sudan Foundation, which sends money to people in Sudan, the money raised through the Cow Project must contribute to the Lost Boys' education in the Syracuse area.

"100 percent goes right back to them," McMahon said. "We started this and said no, the money doesn't get sent back home. We put a limitation on it as education only."

She says it is a great thing to send money back home, but these men are living in extreme poverty and barely have enough to support themselves. "Dau can afford to send this money back but these other guys cannot, that's why we did the Cow Project," McMahon said.

"These are people who are struggling," Turkon agreed.

Despite the success of the Cow Project, McMahon says support for the Lost Boys has dwindled since their arrival in 2002. "Interest is great, but that's as far as it goes," she said.

Even though McMahon is discouraged by the lack of contribution to the Central New York Lost Boys Foundation, she praises the success the Cow Project has brought to members such as Mathiang.

"It's wonderful, the money they are raising," she said. "We hope to expand the program and help even more Lost Boys."

No one involved in the organization would comment on the amount of money the Cow Project has raised.

Dominic Mathiang now lives in an apartment in the City of Syracuse. His one bedroom apartment on the North Side is a reflection of the man who lives in it. It is simple but neat, the sign of someone who takes little value in material possessions. Christmas lights add festive charm, but there is little else beyond the bare essentials. He keeps his home in order and tries to do the same with his life.

Mathiang takes classes at Onondaga Community College, where he plans to major in Psychology. He applies his education towards his job at St. Joseph's Hospital, where he works with mentally handicapped patients.

The Cow Project is essential in funding his education at OCC. He said without the project he would not be able to go to college.

"The money that comes from the Cow Project helps me for example, with the loan from OCC when they denied me for financial aid, so I had to borrow from the bank,” Mathiang said. “Right now, I am paying money from the Cow Project going to that loan."

Because the money from the Cow Project helps him pay for school, Mathiang was able to save his money to pay for a trip to Sudan this January.

Mathiang said he is going to visit his parents whom he hasn't seen in 20 years. He did not know if his parents were alive until three years ago.

How he found out was a matter of fate. A priest and friend from the Syracuse area took a trip to Sudan to preach at a church, Mathiang said. When speaking about his experience in the United States, the priest mentioned the name 'Dominic Mathiang'. Mathiang's parents were there and immediately recognized it.

"...My last name is well known to my relatives, Mathiang, is a name that is sacred," he said. "When he mentioned that name they were surprised… then they came and asked him more about the name that he mentioned, and he was also surprised because I have the resemblance of my mother."

Mathiang smiled as he spoke about the moment he found out about his parents were alive. "I'm excited," he said. "When he came back he told me the story and I thank God for that."

Although planning to visit Sudan, Dominic Mathiang says he has found his place in Central New York, a home where he can remember where he came from and work towards a better future.

During his time in Syracuse, Mathiang learned how to deal with his biggest challenge.

The snow no longer bothers him and he plans to stay right here.

"I don't want to go anywhere,” he said with a smile. “Nope, I like New York.”

No comments:

Post a Comment